What was the true nature of the Union in 1861?

I. In May, 1777, the Legislature of Virginia passed an act requiring all free-born male citizens, above the age of 16 years, to "swear allegiance to the Commonwealth of Virginia as a free and independent State," and the other States, or most of them certainly, passed similar laws. No one was required by any authority to swear allegiance to the United States, or its government. In 1781, the Articles of Confederation, adopted that year, called the Union "a firm league of friendship," and provided that each State "retained its sovereignty, freedom and independence." In the treaty of peace (1783), Great Britain recognized the United States, mentioning the thirteen States by name, as "free, sovereign and independent States." Nevertheless, Lincoln, with characteristic sophistry, tried to fool people into thinking that the States had never been sovereign.

But against his views may be placed the facts, and the opinion of another man of national ideas, far his superior in every way - John Marshall - who in a noted case (Gibbons versus Ogden), declared the Union previous to 1787 a league.

II. John Marshall never resorted to rhetoric or dishonest sophistical argument like Lincoln, but his intense party spirit led him often unto untenable positions. As a member of the Federalist party, he espoused the British doctrine, "once a citizen, always a citizen," denied the Jeffersonian slogan "free ships make free goods," wanted, like the other Federalists, to make the common law a part of the law of the United States, and stood for aristocracy, instead of democracy, as the correct principle of government. All Marshall's views on these subjects stand repudiated by even the present intensely consolidated government of the United States.

So when in the same case (Gibbons vs. Ogden) he reasoned that under the new constitution the Union lost the character of a league, he simply spoke as father to the thought, and .appeared to forget that, if the Union was a league of sovereign States anterior to 1787, as he said it was, the States could not lose that character without some express provision in the new constitution to that effect. It is a fundamental provision of public law that in construing grants from sovereign States, nothing can pass by mere implication or inference (Brown's Legal Maxims, p. 260); Vattel, 2nd Book, chapter SVII, sect. 305-308). And this is especially true when the grant concerns so serious a matter as the sovereignty of the State.

Now no one can show any express revocation of sovereignty in the constitution, and Marshall's argument proceeds by way of implication or inference from powers in the constitution which may be explained wholly otherwise. To reason that from a mere change in the operation of the government or distribution of the powers, the sovereignty can be destroyed, is absurd.

There is no real antagonism between a Federal government of despotic power and a Union of sovereign States, and the difference between the articles of Confederation and the Constitution of 1787 lies not in the nature of the Union but in the grants of power. To render this perfectly plain, suppose there was a clause added to the present constitution, "And this Union is a league from which each State may peaceably withdraw," how would this provision interfere with the operation of the Federal government, as long as the States chose to remain together?

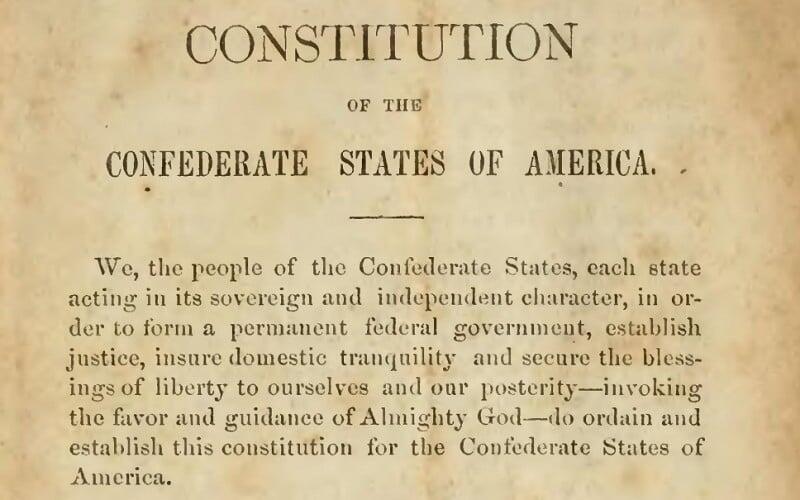

The Confederate Constitution was a mere copy of the Federal Constitution, created "a government proper," but no one has denied that its object was to establish a league of sovereign States.

III. Not only was there no express provision in the constitution or the amendments by which the States surrendered their sovereignty, but there were provisions in it which declare and defend that sovereignty. The seventh article declares that the parties to this constitution are "the States so ratifying the same," and the tenth amendment repels all implications hostile to sovereignty by declaring that "the powers not delegated to the United States by the constitution, nor prohibited to the States are reserved to the States or the people respectively." No one was ever required by the Constitution to swear allegiance to the Federal government or the United States.

How was secession connected with sovereignty?

As members of a league, each State, in the exercise of its sovereignty, by which its will is meant, had a right, under the law of nations, to withdraw from the Union at any time, for reasons to be judged of by itself. But this did not relieve it from its share of the public debt or other obligations incurred as a member of the league, and these were the proper subjects of negotiation. The denial of the right of secession was a denial of sovereignty, and secession was an obvious power reserved to the States under the tenth amendment. Indeed, three States � Virginia, Rhode Island, and New York � in their ratification of the constitution expressly reserved the right of secession, and this reservation, according to the rules of law, enured to the benefit of the other States as well.

William Rawle, who stood at the head of the bar of Philadelphia, published in 1825 a book on the Constitution, in which he showed very conclusively the constitutionality of secession, and this book was used as a textbook to teach the young officers at West Point. (Tyler's Quarterly, XII, p. 87.)

:Confederacy::Confederacy::Confederacy::Confederacy::Confederacy: